Oswald Edwin Ladbrooke

Memories with kind permission of Peter Ladbrooke

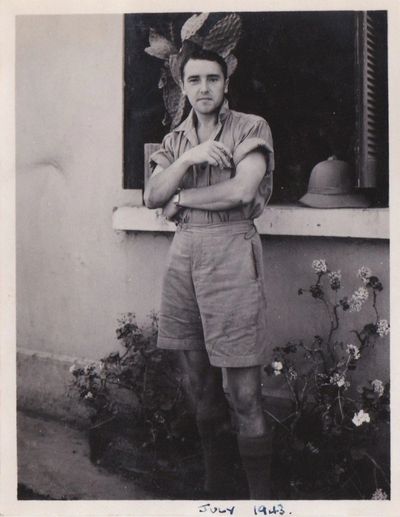

An official government document of August 1943 (my birth certificate) gives my father’s occupation as “Corporal RAF (Admiralty)”. At the time he was in North Africa serving with 624 Squadron (or its predecessor, Flight 1575) – perhaps not the occupation the wider public needed to know about. By then he was a sergeant and, although he was ground staff, he had been issued with full flying kit and, I believe, a service pistol.

A Post-War Excursion

In the early 1950’s, with the acquisition of a small car, one of the first trips my father wanted to make was to Tempsford in Bedfordshire. I went with him, curious as to know why. The answer, which meant little to me then, was that he had been posted there for a time with the RAF in the war. As far as I remember all we did was stand by the roadside and peer across fields to what had once been an RAF airfield. There was not much to see.

The Desk – and a Photograph Album

Father had a desk which was out of bounds to me. Inquisitiveness meant, however, that when Dad was at work I would do what I had been told not to do – and found a brown book, evidently handmade, containing photographs of bomber aeroplanes in a dusty place, some damaged, some crashed, what looked like funeral services, men in RAF uniform, servicemen in hot weather attire, and pictures of strange-looking buildings. I was 15 years old before I owned up and asked what this record was about. He had made the album from such materials as were available while on active service in North Africa and Italy in which to keep a record of what life was like. Beginning then, and for the rest of his life, he would re-live events that never left him and which changed him.

Tempsford, the Admiralty? and Selection of Aircrew

He never spoke about what he did at Tempsford – perhaps because there was nothing he could tell. The following paraphrased account suggests he was initially engaged administratively in selecting aircrew for what we nowadays understand to be Special Duties:

I was part of an interview board assessing would-be volunteers for irregular operations flying heavy bombers – that’s all we had been told. We were located on a high floor in a tall building (I think in London; was this the Admiralty building perhaps?). Those coming for interview were told not to use the lift but the stairs.

We had a raft of questions to ask, one of which was “How did you get up here?”. The answer we wanted to hear was “By the lift…”.

Another was “How many lace holes do you have in your shoes?”. Anybody who looked to count them was marked down; the type we were after would leave us in little doubt they thought such a question had no bearing on why they were there. The idea was to identify the non-conformists – men who did not need to live by a rule book but could rely on their own initiative.

If I remember correctly, Australians fitted the need rather well.

Deployment to North Africa and Italy

The earliest date on a photograph taken in North Africa by my father, Sergeant O.E.Ladbrooke, is June 1943. It was taken at Blida in Algeria. In June 1943 the unit was Flight 1575; it was raised to squadron status in September 1943 as 624 Squadron.

The brief annotations on his photographs trace the Squadron’s movement from Blida to Tunis (November 1943) showing tented camps at Bizerte and Sidi Amor (both near Tunis), Tocra (Benghazi, December 1943) , Brindisi (Italy, January 1944) and return to Blida (February 1944 until September 1944). (Note: the dates given here are those on the photographs; they are not the dates of the beginning or end of redeployment.)

Not once did my father give any indication that he knew what 624 Squadron was founded to do. All he knew was that it was an irregular unit – not flying the massed raids of Bomber Command – but mounting operations by lone aircraft to destinations unknown to him (it was only after his death in February 2001 that I set about finding out what 624 did).

Experiences with Flight 1575 and 624 Squadron

Unable to disclose his whereabouts, my mother had to guess where my father was; she guessed Scandanavia and knitted him heavy woollen sweaters - not really the attire for the relentless North African daytime heat. That was the lighter side of life. As to the darker side, paraphrasing:

Living in tented camps in North Africa held its own risk: scorpions, the sting of which is deadly. We had to be thorough in checking our tents, bedding and clothing - you didn’t want to be stung by one of those things. One way of getting rid of them if you found one was to encircle it with a ring of petrol which you then set light to. Surrounded by fire the scorpion would sting itself to death. Unpleasant, but at least it then wasn’t going to sting you.

On one occasion, in flight our Halifax was struck by lightning. There was not much consequence – flashes of electrical discharge rippled around the inside of the fuselage and that was it.

One of the duties was collecting together the personal effects of aircrew killed and informing the next of kin. Crews went out but never came back, and it left him numb. Occasionally, when the weather closed in a returning aircraft could be heard overhead but, unable to identify the landing strip, it would overfly and crash into the high ground of the Atlas mountains. The loss of men he knew, liked and respected had a lasting effect on him. As a direct result he had difficulty in the post-war years in forming friendships or, as he put it

Making friends is something you learned not do.

Against this general background, two events left their mark:

When running up the engines for take-off the port inner (I think he said) shed its propeller (or piece of propeller) which scythed through the cockpit and severed a crew member’s arm (I believe he said the pilot’s). The severed arm finished up on the ground. By the time we got to it somebody had stolen the watch off it. That really shook my faith in human nature.

The second involves the last-minute replacement of a crew member. (The account as I remember it raises a question though. Whereas in Bomber Command the crew of an aircraft came together by consent among themselves and thereafter always flew together, did the same apply in the Special Duties squadrons, or was there a core (pilot, navigator…) around which other crew members were assembled on an ad hoc basis, or was illness or loss the only way in which a regular crew member could be replaced, as in the main force?).

A rear gunner had ‘one more’ to do before being released from operations. He had a close friend, also a rear gunner, whose name was on the crew list posted for an operation. After a little persuasion, and in the belief that he was doing a favour, the nominated rear gunner rubbed out his own name and substituted that of his good friend. The aircraft was lost, leaving the originally-named unable to accept anything other than that he had killed his friend. It made you think: “Don’t do anybody a favour” and for years my father seemed to live that way.

Disbandment

624 Squadron was disbanded on 05 September 1944. As father continued to serve in one administrative capacity or another there are many later photographs taken in Algiers, Portici (Naples), Sorrento (Naples), Rome, Legnano (Milan), Lake Como and Klagenfurt (Austria).

Last Words

In addition to his photographic record the following of my father’s effects survive: his Service and Release Book, Identity Tags, Service Medals, kit bag, hair brush (stamped with his service number) and flying boots. His flying jacket and helmet he wore in post-war years when riding his motorcycle (I do not know what became of them thereafter). The service pistol he surrendered upon his release, if not before.

Oswald Edwin Ladbrooke, born 23 February 1912, died 14 February 2001.

Sergeant RAF, Service Number 926925. Volunteered 13 July 1940, Released 12 March 1946.